- comparisons of preaching practices across the Atlantic world

- the contents or contexts of individual sermons, sets of sermon notes, or sermon collections

- sermons related to particular Biblical passages

- particular genres of, or occasions for, sermons

- sermons preached at particular venues or in specific regions

- the responses of auditors and/or readers of sermons, or note-taking practices

- women’s relationships with sermons and preaching

- comparative perspectives on sermon manuscripts in other languages or religious traditions

- preaching patterns and methods

- compilers, collectors, or owners of sermon manuscripts

- related manuscript materials, such as liturgical, doctrinal and devotional manuscripts

- perspectives of librarians or archivists on manuscript sermon collections

- use of digital tools and methods to study sermon manuscripts or related data

- related early modern digital resources

Monday, 30 October 2023

Call for papers: Preachers, Hearers, Readers, and Scribes: New Approaches to Early Modern Sermons in Manuscript

Friday, 23 June 2023

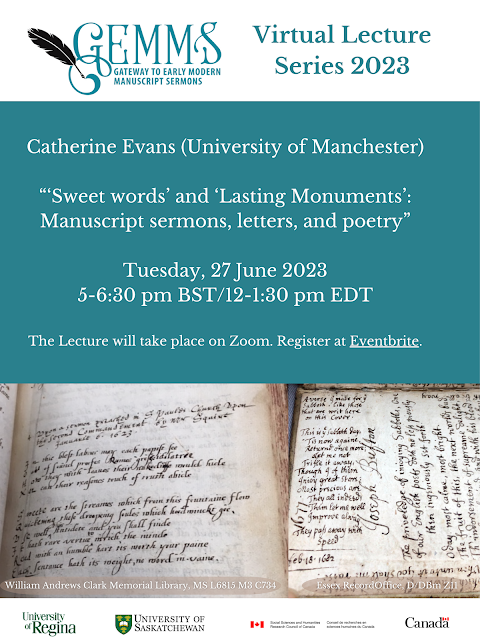

GEMMS Virtual Lecture: Catherine Evans, "'Sweete Words' and 'Lasting Monuments': Manuscript sermons, letters, and poetry"

There is only 4 days left before the next GEMMS virtual lecture by Catherine Evans, ""'Sweete Words' and 'Lasting Monuments': Manuscript sermons, letters, and poetry" on Tuesday, June 27!

To join us live on Zoom or to the receive a link to the recording, register at https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/catherine-evans-manuscript-sermons-letters-and-poetry-tickets-546390688257

We hope you can join us!

Lecture abstract:

“A verse may find him whom a sermon flies”, as George Herbert writes in The Church Porch. Herbert may have been pre-emptively batting away criticism for taking time away from composing and delivering sermons to dedicate himself to the poetic arts, suggesting that for some poetry would be more effective as a spur to devotion. This talk will consider the relationship between verse and sermon from the perspective of the lay reader, examining manuscript poetry written in response to hearing or reading sermons. These include poems by a wife about her clergyman husband’s preaching, verses by an Essex cloth worker on his own sermon attendance, and a reworking of a funeral sermon in rhyme. If, as Arnold Hunt has discussed, we need to consider how sermons taught their hearers to listen to rhetoric and recall the word of the Bible, how did they also move them to create new texts and transform them into poetry?

In A Call to Come to Christ, a poem found in a religious manuscript miscellany once belonging to Lady Betty Bruce Boswell, Elizabeth Melville rewrites Christopher Marlowe’s The Passionate Shepherd to His Love: “Come live [with me] and be my love/ And all these pleasures thou shalt prove… O loath this life and live with me/ This life is but a blast of breath”. She transforms the words of “lawless lust” and “love profane” into “that living well/ Which shall thy dwining [thirsting] drowth expell”. Research for GEMMS has demonstrated that manuscript sermons often sit beside all sorts of “profane” material: personal account books, recipes, and extracts of amatory verse to name a few. By exploring the poetry that sits alongside sermons, and in many cases was inspired by them, this talk will situate sermons within the broader literary landscape of the time.

Wednesday, 31 May 2023

GEMMS Virtual Lecture: Lucy Underwood "Preaching the Counter-Reformation in England"

There is only a week until Lucy Underwood's virtual lecture "Preaching the Counter-Reformation in England" on June 7!

Register today to join us live or receive a link to the recording later.

Lecture abstract:

"After the accession of Elizabeth I, Catholicism became a prohibited religion in England. Yet, from the 1570s onwards, the project of the ‘English Mission’ was to bring the Catholic Reformation, which in this case may be properly called a ‘Counter-Reformation’, to England. Like proponents of Catholic Reform elsewhere, they knew the value of preaching, but like other Catholic practices, Catholic preaching happened in the shadows, passing unnoticed except when people got caught. It is therefore difficult for historians to trace: we know it happened, but when, where, how often and – crucially – what was preached has been very difficult to know. There has been more scholarly focus on the practices Catholics used to substitute for preaching and sacraments, when access to a priest was dangerous and infrequent – the printed word becoming especially important.

However, sources on Catholic preaching do exist. This lecture will trace those clues, and will examine the texts of Catholic sermons which survive from the century following the Protestant Reformation – some preached in English Catholic institutions in exile, others, it seems, in England itself. What missionary priests preached, and what English Catholics heard from them, are key to understanding how the Counter Reformation helped to create Catholic communities which could survive in Protestant England."

Monday, 8 May 2023

GEMMS Virtual Lecture: Mary Morrissey "Sermons in series and fragments" 11 May 2023

There is only three days until Mary Morrissey's virtual lecture: "Sermons in series and in fragments: GEMMS, the archive, and finding the Spital and Rehearsal sermons"!

Tuesday, 13 September 2022

Job Opportunity: Research Assistant in the UK

GEMMS is a group-sourced, online, bibliographic database of early modern (1530-1715) sermon manuscripts in the UK and North America (https://gemmsorig.usask.ca/). The role of the Research Assistant is primarily to collect metadata for the database in selected UK repositories identified by the principal researchers. The Research Assistant also may have the opportunity to present research, to participate in promoting GEMMS, and to conduct workshops for groups of potential contributors and users.

Collect metadata on

sermon manuscripts at libraries and archives in the UK (repositories to be

selected in consultation with the principal researchers) and enter this data

into the database.

Advise principal

researchers of difficulties encountered and significant discoveries of

additional materials.

Check and correct

data currently in the database.

Contribute

to GEMMS’s social media, including short posts and blogs, to highlight the

content of GEMMS.

Compensation:

The Research Assistant will be compensated £17.50/hour to a maximum of £4200 plus

travel expenses as required. In consultation with the principal researchers,

the student will develop a mutually beneficial research schedule.

Qualifications:

Candidates must be

enrolled in a PhD program in a related field at a UK university. Candidates whose

work involves the use of early modern British sermons and/or who have a

background in early modern British ecclesiastical history will be preferred.

Candidates also must

be willing to travel within the UK to conduct research and potentially internationally

to attend conferences.

Candidates must be

able to communicate effectively both orally and in writing and must be able to

work well independently.

Candidates must have

accurate word processing skills and be attentive to detail. Familiarity with

databases is an asset.

Candidates with

training in early modern British paleography will be preferred. Some knowledge

of Latin and/or Greek would be useful, though not required.

Application procedure:

Applications

will be accepted until November 4, 2022. We anticipate hiring to be completed

in November and work to begin in January 2023, though an earlier start date may

be possible.

Please submit a cover letter outlining your qualifications and availability, a current CV, and the names and contact details for two referees to jeanne.shami@uregina.ca or anne.james@uregina.ca.

Job Opportunity: Research Assistant in the US

The Gateway to Early Modern Manuscript Sermons (GEMMS) project is seeking a student enrolled in an American PhD program in a related field of study (including but not limited to early modern English literature, social, political, and religious history, theology, and book history) to assist with data collection. The duration of the position is twelve months, with a 3-month probationary period. There is a possibility of extending the contract. The researcher will work approximately 20 hours per month during the term of the contract, though the number of hours is negotiable with the principal researchers.

GEMMS is a group-sourced, online, bibliographic database of early modern (1530-1715) sermon manuscripts in the UK and North America (https://gemmsorig.usask.ca/). The role of the Research Assistant is primarily to collect metadata for the database in selected US repositories, primarily in the northeast, identified by the principal researchers. The Research Assistant also may have the opportunity to present research, to participate in promoting GEMMS, and to conduct workshops for groups of potential contributors and users.

Duties:

Collect metadata on

sermon manuscripts at libraries and archives in the US (repositories to be

selected in consultation with the principal researchers) and enter this data

into the database.

Advise principal

researchers of difficulties encountered and significant discoveries of

additional materials.

Check and correct data

currently in the database.

Contribute

to GEMMS’s social media, including short posts and blogs, to highlight the

content of GEMMS.

Compensation:

The Research Assistant will be compensated $21 USD/hour to a maximum of $5040 plus

travel expenses as required. In consultation with the principal researchers,

the student will develop a mutually beneficial research schedule.

Qualifications:

Candidates must be

enrolled in a PhD program in a related field at an American university.

Candidates should live in or near New Haven, CT; or Boston (including

Cambridge), MA.

Candidates will be

preferred if their work involves the use of early

modern British or colonial sermons and/or they have a background in early

modern British or colonial ecclesiastical history.

Candidates must also

be willing to travel within the Eastern US to conduct research and potentially internationally

to attend conferences.

Candidates must be

able to communicate effectively both orally and in writing and must be able to

work well independently.

Candidates must have

accurate word processing skills and be attentive to detail. Familiarity with

databases is an asset.

Candidates with

training in early modern paleography will be preferred. Some knowledge of Latin

and/or Greek would be useful, though not required.

Application procedure:

Applications

will be accepted until November 4, 2022. We anticipate hiring to be completed

in November and work to begin in January 2023, though an earlier start date may

be possible.

Wednesday, 25 May 2022

‘My Doubts and scruples in Religion’: The Recantation of John Gibbs in the GEMMS Database (GEMMS Sermon #25000)

But ’tis no matter, let what will, befall,

A Recantation Sermon payes for all.[1]

Sermon#25000 in the GEMMS database is a recantation sermon delivered by John Gibbs, rector of Gissing, Suffolk, on 2 December 1688 at his own church. This entry represents an extremely rare example of a full transcription of a recantation sermon in manuscript dating from the post-Restoration period.[2] This blogpost considers briefly this significant genre of sermon before discussing Gibbs and the circumstances surrounding his recantation.

Recantation sermons were prevalent in 1530–1715, the period covered by the GEMMS project.[3] If a preacher had been tried and convicted of heresy, he was required to recant and to make a public penance, frequently reading a confession at the event and sometimes delivering a sermon. On some occasions, the sermon would be preached by another clergyman in the presence of the guilty party. In the early years of the Reformation, refusal to recant would often result in execution by burning (see Figure 1).[4] Recantation sermons therefore constitute valuable sources for scholars researching religio-political censorship, the activities of wayward clergy, and the consequences of heresy in the long English Reformation.

Within

the GEMMS database, there are three examples of inflammatory sermons which caused

their authors to be condemned and subsequently to recant.[5] However, full

handwritten transcriptions of recantation sermons appear to be scarce. This is

somewhat surprising as recantation sermons could prove extremely popular in

print; Mary Morrissey notes that Theophilus Higgons’s recantation sermon,

preached at Paul’s Cross on 3 March 1611, ‘went through three editions in the

year of its delivery, something that few sermons achieved’.[6]

Dating from a somewhat later period than Higgons’s sermon, one full transcription of a recantation sermon within the GEMMS database can be found within the commonplace book of William Lloyd, bishop of Norwich (British Library, Add MS 40160 / GEMMS-MANUSCRIPT-001583). Lloyd was later to be deprived himself, on account of being a nonjuror, on 1 February 1690.[7] The scribe has not been identified; however, at the top of the first page of the sermon transcription, a title has been provided in Lloyd’s own hand: ‘Mr Gibbs his recantation sermon preached by my order att his parish church att Gissing’ (see Figure 2).[8]

|

| Figure 2: The first page of John Gibbs’ recantation sermon. British Library, Add MS 40160, f. 49r. |

‘Mr

Gibbs of Gissing’ was John Gibbs, who was admitted pensioner at Corpus Christi

College, Cambridge in 1660, graduating B.A. in 1663/4 and proceeding M.A. in

1667. From 1668 until 1690, he was rector of Gissing, Norfolk; in 1671, he also

became rector of Banham, Norfolk.[9] According to Francis Blomefield, he had

been presented to Gissing by King Charles II and was ejected, like Lloyd, as a

nonjuror in 1690. Moreover, he was ‘an odd but harmless man, both in life and

conversation’. After his ejection, he lived in the north porch chamber at the

church at Gissing, positioning his bed in order that he could see the altar;

when he died, he was buried at Frenze, Norfolk.[10] In his short account of

Gibbs, Blomefield fails to mention one crucial detail; namely, that Gibbs had apparently

considered converting to Catholicism in 1687 before returning to the Church of

England.[11]

Gibbs’s temptation to convert must be understood within the religio-political setting of the late 1680s. The position of the High Church, led by bishops such as William Lloyd, was becoming increasingly undermined by the Catholic James II.[12] However, the question of whether Gibbs was directly motivated to join the Catholic Church owing to James II’s Catholicism and its impact upon the clergy is difficult to answer without concrete evidence.[13] The events leading up to Gibbs’ recantation remain obscure; it is not certain whether Gibbs confessed to Lloyd himself or if Lloyd had received information about Gibbs from another source. Furthermore, the exact timing of Lloyd’s condemnation and order for Gibbs’s recantation is nebulous; we cannot be sure whether Lloyd had to wait for some time before he was able to carry out his censure of Gibbs. James II eventually fled England for France at the end of December 1688, arriving on Christmas Day. Gibbs’s recantation sermon was preached, in any case, at an opportune moment, a time when the fall of James was imminent.

Within the commonplace book, the recantation sermon is preceded by a list of John Gibbs’s ‘Considerations moveing to the Church of Rome with Answers thereunto’.[14] There are seven principal reasons why Catholicism appealed to Gibbs; to provide just a couple of examples, he argued that ‘Protestants seem to imitate ancient Hereticks seeking Religion in the way of Science and reason, to the Contempt of Church Authority.’ Besides, the invocation of Saints was ‘a splendid, and magnificent way of worshipping of God’.[15]

The biblical text for Gibbs’ recantation sermon, chosen by Lloyd, was an extract from Luke 22:32 (‘[…] and when thou art converted, strengthen thy brethren’).[16] Gibbs opened his sermon by referring to Peter as ‘a Great instance of humane frailty, and Infirmity in thrice denying his Lord and Master’. He proposed in the first instance to speak of Peter’s ‘State and Condition before his Fall’, his Fall itself, and of his repentance and conversion.[17] Referring to Peter’s denial of Christ, Gibbs argued that one of the causes of his Fall was ‘his Pride and Confidence of himselfe, and in the power of his own will’; what is more, ‘[h]is faith was not strong enough, nor his contempt of the world great enough’. Gibbs posited that Peter’s Fall was ‘not a Totall Apostacy’, but rather ‘a timerous Negation of the Faith’.[18] Once the sermon had drawn to a close, Gibbs continued by admitting that he had been ‘makeing Adventures in Religion, to find out the safest way to Heaven’. ‘One great mistake in this Adventure’ was his lack of communication with William Lloyd regarding his ‘Doubts and scruples in Religion’; his transgressions may otherwise have been thwarted. He proceeded to denounce ‘the Pompe and Ceremony’ of Catholicism with its ‘great inconvenience of haveing all performed in an unknown tongue’, concluding that he had erroneously admired ‘the things of Strangers, to the prejudice of those of his own Country’.[19] The names of ten churchwardens, witnesses to the sermon, follow this statement.

John Gibbs was swiftly forgiven. A letter from William Lloyd, addressed to William Sancroft, archbishop of Canterbury, and dated 4 December 1688, describes Lloyd’s impression of Gibbs as a ‘melancholy pious man’ (see Figure 3).[20] Tantalisingly, Lloyd’s letter also outlines his reaction to Gibbs’s recantation sermon, which was apparently satisfactory to the extent that he recommended its publication. Whether Sancroft approved of Lloyd’s suggestion to publish the sermon is not known; there are no surviving records relating to the sermon’s publication.[21]

|

| Figure 3: Letter from William Lloyd to Archbishop William Sancroft, 4 December 1688. Bodleian Library, MS. Tanner 28, fol. 274. |

Recantation

sermons continued to be preached later in the period and beyond until 1779 when

the genre ceased, and many of these were never published.[22] It remains to be

seen whether further manuscript witnesses, or reports, of these fascinating

sermons dating from the years 1530 until 1715 will be uncovered as the GEMMS

Team resume on-site visits to archives in 2022.

References

[1] Anonymous, [A] Pulpit To Be [Let] (London, 1665). English Broadside Ballad Archive, EBBA 36352.

[2] For the scarcity of extant recantation sermons in manuscript dating from post-Restoration England, see Simon Lewis, ‘“The Scum of Controversy”: Recantation Sermons in the Churches of England and Ireland, 1673–1779’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 55.2 (2022), 215–33 (p. 216).

[3] Early modern recantation sermons, particularly those preached in the late seventeenth century, have received comparatively little scholarly attention. See Michael C. Questier, ‘English Clerical Converts to Protestantism 1580–1596’, Recusant History, 20.4 (1991), 455–77 (pp. 470–71); Susan Wabuda, ‘Equivocation and Recantation During the English Reformation: The ‘Subtle Shadows’ of Dr Edward Crome’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 44.2 (1993), 224–42; Michael C. Questier, Conversion, Politics and Religion in England, 1580–1625 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), ch. 6; Mary Morrissey, Politics and the Paul’s Cross Sermons, 1558–1642 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 113–20; Kate Roddy, ‘Recasting Recantation in 1540s England: Thomas Becon, Robert Wisdom, and Robert Crowley’, Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, 39.1 (2016), 63–90. Note that Morrissey focuses on recantation sermons principally preached by clergy converting from Catholicism until the 1640s, while Kate Roddy conducts close readings of recantation texts from the early years of the English Reformation.

[6] Theophilus Higgons, A Sermon Preached at Pauls Crosse the third of March, 1610 (London, 1611); Morrissey, p. 118. See also Alec Ryrie, The Gospel and Henry VIII: Evangelicals in the Early English Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 82; Lewis, p. 216.

[7] Stuart Handley, ‘Lloyd, William (1636/7–1710)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn (2004), <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/16859> [accessed 3 March 2022]. For a summary of the contents of Lloyd’s commonplace book up to f. 171v, see Peter Smith, ‘Bishop William Lloyd of Norwich and his Commonplace Book’, Norfolk Archaeology, 44.4 (2005), 702–11.

[8] British Library, Add MS 40160 (GEMMS-MANUSCRIPT-001583; GEMMS-SERMON-025000), f. 49r.

[9] Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1500–1714, 4 vols (Oxford: Parker, 1891), Vol. II, p. 561; John Venn and J. A. Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, Part I, 4 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922–27), Vol. II, p. 209. See also ‘John Gibbs (CCEd Person ID 12516)’, The Clergy of the Church of England Database 1540–1835 <http://www.theclergydatabase.org.uk> [accessed 4 February 2022].

[10] Francis Blomefield, ‘Hundred of Diss: Gissing’, in An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 1 (London, 1805), pp. 162–81. British History Online, <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-hist-norfolk/vol1/pp162-181> [accessed 4 February 2022]. For Gibbs’ ejection, see also ‘A Catalogue of the English Clergie and other Schollars, who haue refused to take the New Oaths’, British Library, Add MS 40160, ff. 74r–78r (f. 74r).

[11] Letter from William Lloyd to Archbishop William Sancroft, 14 November 1688, Bodleian Library, MS. Tanner 28, fol. 248.

[12] John Spurr, The Restoration Church of England, 1646–1689 (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1991), ch. 2; Smith, p. 706.

[13] For the promotion of Catholicism in Jacobite sermons, see William Gibson, ‘Engines of Tyranny: The Court Sermons of James II’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 97.1 (2021), 11–24.

[14] British Library, Add MS 40160, ff. 45r–46r.

[15] British Library, Add MS 40160, f. 45r.

[16] Letter from William Lloyd to Archbishop William Sancroft, 4 December 1688, Bodleian Library, MS. Tanner 28, fol. 274 (GEMMS-REPORT-000378).

[17] British Library, Add MS 40160, f. 49r.

[18] British Library, Add MS 40160, f. 49v.

[19] British Library, Add MS 40160, f. 52r.

[20] Smith, p. 706.

[21] Letter from William Lloyd to Archbishop William Sancroft, 4 December 1688, Bodleian Library, MS. Tanner 28, fol. 274.

[22] Lewis, p. 216.

~ Hannah Yip